I spent 5 years — from 1968 to 1973 — building geodesic domes. I first built two domes in Big Sur, then spent two years at an “alternative,“ (i.e. hippy) high school in the Santa Cruz (California) mountains managing a program where we built 17 domes for students to live in. Our book Domebook 2, generated by that experience, went on to sell 160,000 copies.*

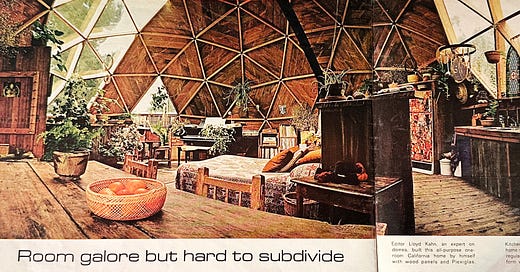

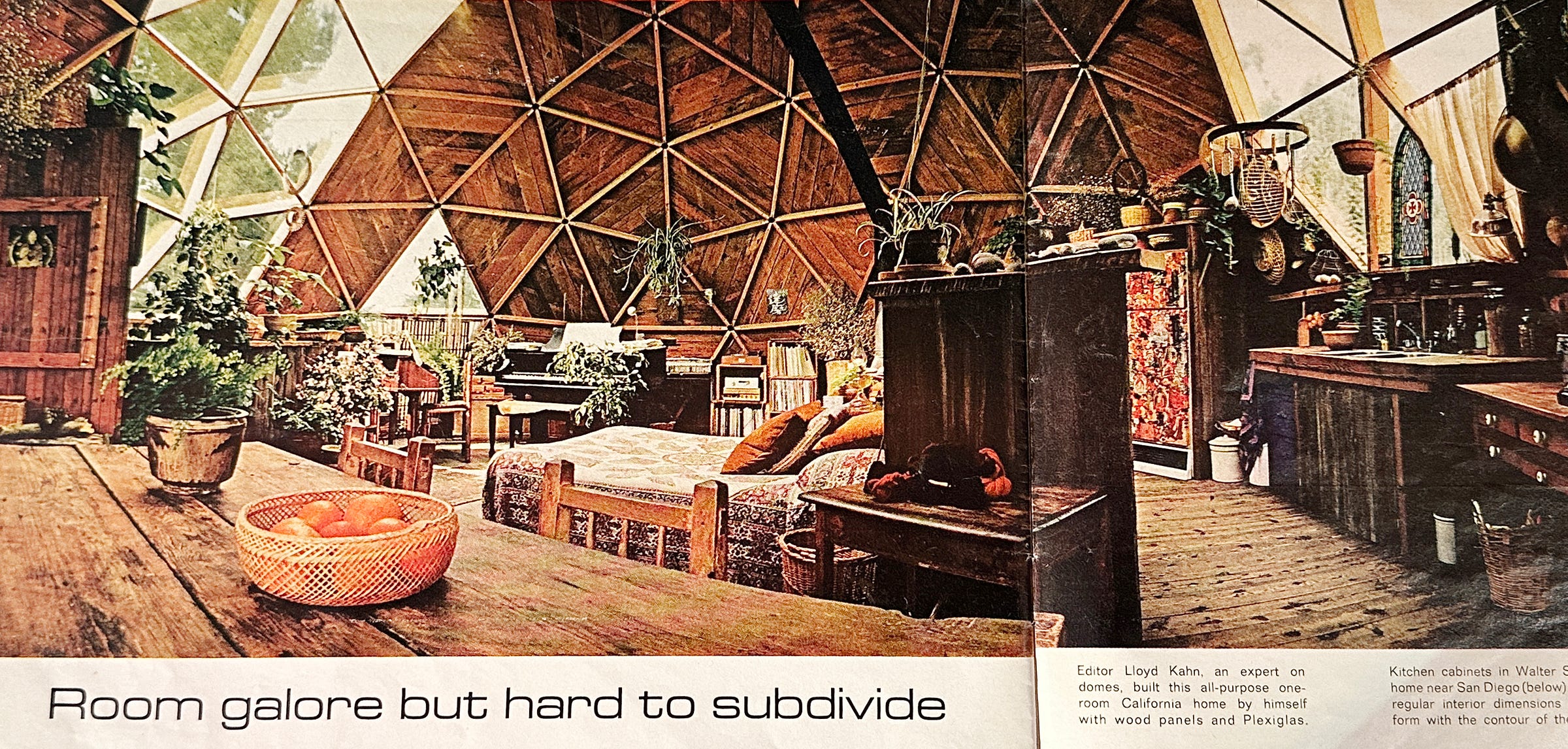

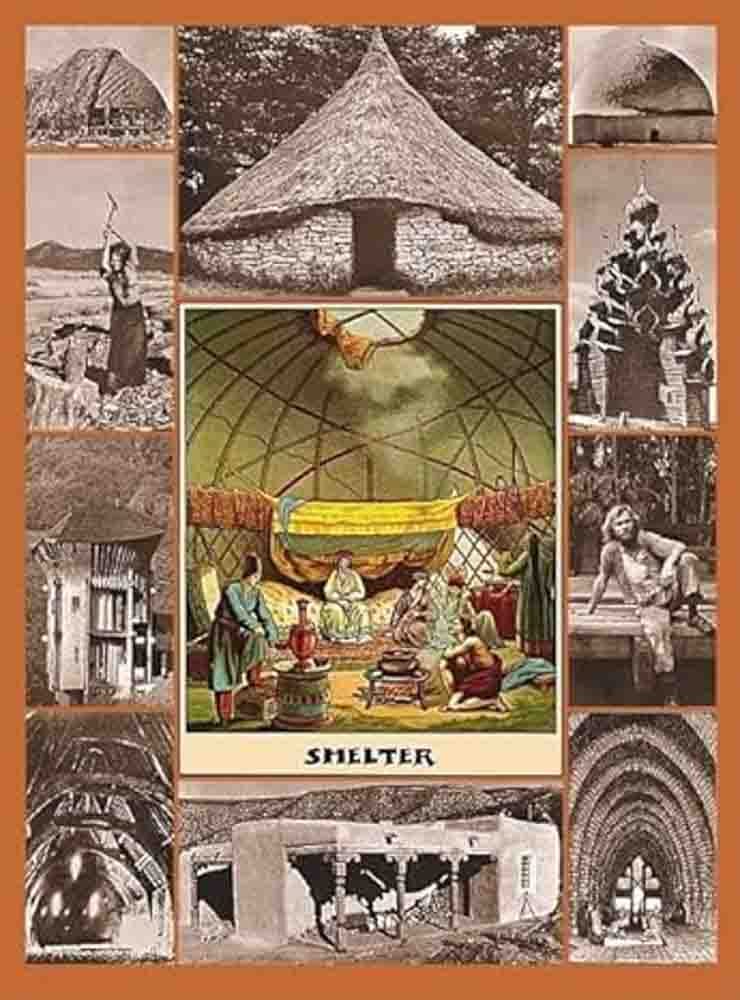

After that, I built a final dome in Bolinas, which was featured in Life magazine:

Also, during the ‘60s, I was interviewed by Time magazine, Rolling Stone, and other publications as the counter-culture spokesman for domes, which we touted as a new and better method of building homes. Domes were built off-grid, on communes, and were associated with conservation of resources and alternative sources of energy. Domes were hip.**

Getting Into Domes- A Very Condensed History

Stepping back in time: in 1967, I was foreman on a job building a large house out of bridge timbers on a 400 acre ranch in Big Sur.

On a stormy weekend, Buckminster Fuller gave a three-day seminar at nearby Esalen Hot Springs and, among other things, talked about lightweight geodesic domes.

I was smitten, partially by the fact that we were struggling to frame a structure with heavy timbers, and I started building domes on my property at Burns Creek (2 miles north of Esalen) in Big Sur.

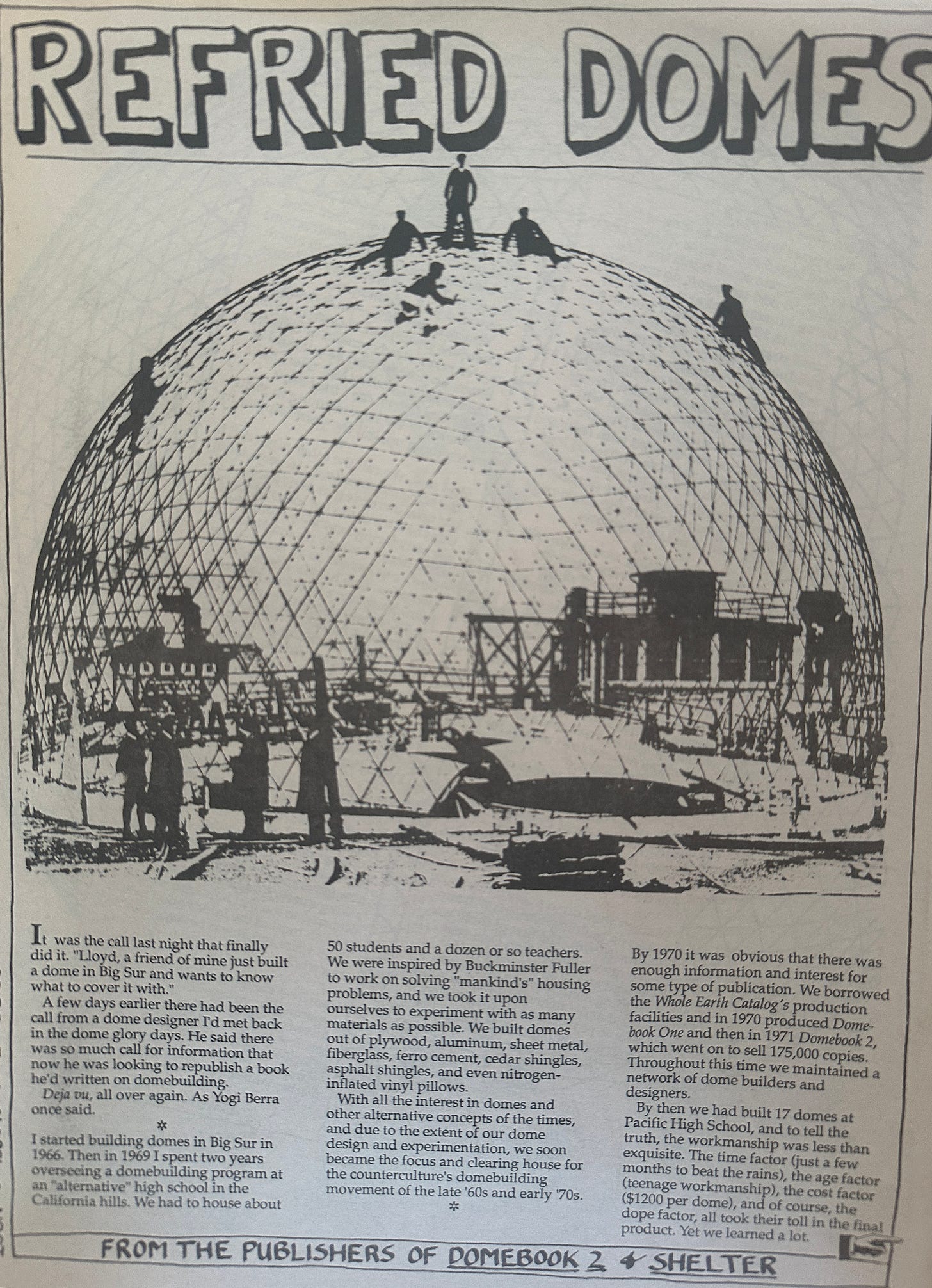

About a year later, I met the directors of Pacific High School, located on a 40 acre parcel of land in the Santa Cruz Mountains. They wanted to build living quarters for students and create a boarding school. We moved there from Big Sur and, over the course of two years, built 17 geodesic domes, experimenting with various materials.

It was a natural story for the media, what with all the publicity about the countercultural revolution and all the new things being tried out in those heady days. Here were ecologically-minded 17-year old long-haired kids building their own homes.

One Last Dome

I wanted to build one more dome after I left the school in 1971, not controlled by communal consent or lack of funding, so I built the dome shown at the top of this article and, if you forgive the self-aggrandizement, I consider it — with its warm used wood interior and silver hubs — the most aesthetically pleasing and livable dome built to that time.

I realize in retrospect that I was trying to make domes more human, less sterile.

Seeing the Light

Yet I kept having more and more nagging doubts about the suitability of dome homes as time passed, until I had my eureka moment one warm spring day.

I had taken some mescaline and hiked up the nearby Copper Mine Canyon. It was a beautiful day and I tuned into the trees and watched water skeeters skimming across the creek and then started back down towards the road.

I came upon a pristine meadow, and thought: what if a dome had been built there, inspired by our book, and it was falling apart, plastic parts littering the landscape, and I would be responsible.

“Are You Crazy?”

As soon as I got home, I called Don Gerard, my agent with Random House (where the book was still selling briskly), and said, “Don, I’m taking Domebook 2 out-of-print.”

”Are you crazy?””

“Maybe I am, Don, but I don’t want any more domes on my karma.”

The Birth of Shelter

That’s what I mean when I say I had to admit I was wrong in front of 1/4 million people. “Hold everything, you guys, I was wrong. Domes are a much less practical way to build than conventional stud frame construction, as well as other standard (and alternative) methods of homebuilding.”

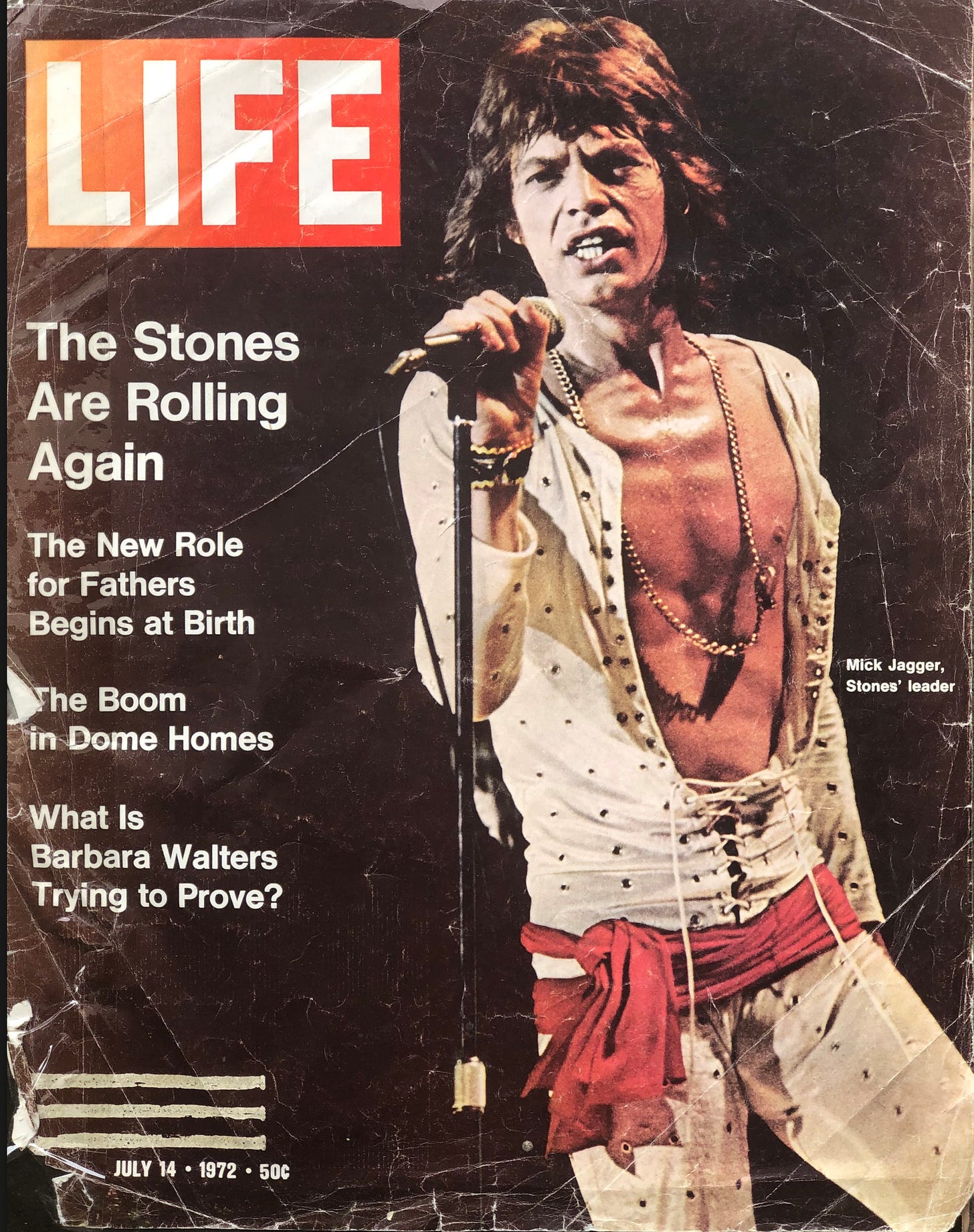

And with that, in 1972, I set out with my friends, architect Bob Easton and photographer Jack Fulton to gather material for the book that eventually became Shelter.

(In October, 1989, I summarized my updated thoughts on domes in a newsprint publication titled Refried Domes, in which I said: “Part of of any experimental process is the possibility of failure.” If you go to this link, maybe skip to the end and read “Domes vs.Rectangles.”)

“Mamas, don’t let your mathematicians grow up to become builders . . .”

The Catharsis Of Admitting You Were Wrong

In the process, I learned one of the most valuable lessons in my life: if you’re wrong, admit it.

I think we’re programmed to defend a position or concept once stated. We don’t even reconsider, but just go into defense mode.

But here, because of the magnitude of the audience, and being responsible for builders wasting a lot of resources, I couldn’t weasel out of it.

And lo and behold, ever since, I’ve had no trouble admitting I’m wrong — it’s cleansing, like jettisoning unneeded baggage. A couple of examples:

For maybe 40 years, I didn’t think smoking cannabis was bad for your lungs. Well, guess what? It is. Not nearly as bad as tobacco, but still…. I wrote about it here.

For decades, I swore by stick shift cars. No automatic transmissions for me. But when I bought a 1999 Mercedes 320E (for $3500) three years ago, I loved the automatic transmission. (This model, by the way, is an incredible under-the-radar car.)

A lot of times, people have said to me, “But I thought you said…”

“Yes, that’s what I thought then, but this is what I think now.”

Admit you’re wrong, for Christ’s sake, and get on with your life.

“Success is the ability to go from failure to failure without losing your enthusiasm”

―Winston Churchill

*If you figure 2 people read every copy, that’s 320,000 people. On communes, for example, a dozen or more people were reading every copy.

**There’s a saying: “The ‘60s happened in the ‘70s,” but it’s only partially true. The ‘60s happened in the ‘60s and the ’70s.

‘

Lloyd, we have talked to each other before. Your resolution concerning domes for houses came about the same time as it hit me in the head too! The resolve was your 1972 Shelter book, which led me to a 50 year experience as a building Contractor / Carpenter. It is truly a Master Piece of work, and a gem to the Art of building structure's. Thanks again for leading the way into a life experience that has been part of the intuitive nature of the existence of mankind since its inception. Once again, Cheers to you, Lloyd Kahn...

Great article! I was a 17 year old in 1968 helping to build a dome in Rosendale, NY. And then I had an older friend who lived in one. I was intrigued but not impressed...From there - via a circuitous route- I ended up staying with a Masai tribe in Tanzania and visited their mud and wattle rounded homes which the women built. One mzee (old woman) showed me how it all worked. What an eye opener! From there to living in Kyoto and seeing their unique farmhouses out in the country. I never forgot. Lloyd, your subject of shelter is needed now more than ever I think. Keep going!